Colors of Africa: Contemporary Art from the Continent

Mbari Institute

The curator, Mimi Wolford of the MBARI Institute for Contemporary African Art in Washington, DC, also selected four works from the Diggs Gallery permanent collection for the exhibition. The works include batiks by Nigerian female artists Aloke Buraimoh and Nike, as well as a work by the foremost Nigerian Printmaker Bruce Onobrakpeya.

In 1970, Wolford, a graduate of Mills College co-founded Mbari Art, an organization promoting international cultural exchange; and presenting the works of artists from Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, and the United States in prominent museums and institutions in the U.S. and abroad -including three simultaneously at the Corcoran, Renwick and National Museum of African Art. Mbari has arranged over 100 exhibitions. In 1995, Wolford founded the non-profit Mbari Institute for Contemporary African Art (MICAA), a multidisciplinary organization dedicated to the collection, preservation, identification, documentation, and exhibition of work pertaining to the art, craft, and culture of Africa. Its goals are to educate the public, give visibility to African artists, promote and publish research, and act as a permanent repository for the works of contemporary African artists, books, publications, and related materials.

A Word About the Artists

Assembling this show of 38 artists from 18 countries in Africa has been a work of love. I wish to thank all the artists who so generously worked with me, in some cases creating paintings especially for the exhibition. There is a preponderance of work from Nigeria and Ethiopia not only because I lived in both countries, but because there are so many artists in these countries. Bernice Kelly’s1993 book, Nigerian Artists: A Who’s Who & Bibliography documented 350 Nigerian artists who had had at least three important shows. Since that time, many more noteworthy artists have come on the scene, two of whom are included in this exhibition – Victor Ekpuk and Florence Adeyemi.

To view this online presentation of the exhibit's brochure, please use the navigation links at the top of the page. There are 38 pages, one for each artist represented in the Colors of Africa exhibit.

Mimi Wolford

Founding Director

Mbari Institute for Contemporary African Art

Symbols on symbols, around symbols; sand, string, cloth and tissue paper all combined and painted with a palette of natural pigments. In Family Life there seems to be a tent stretched north, east, west and south over the middle portion, a protection if you will, while in Alliance (or Marriage), the two entities are tied together in union by the binding lines in the middle.

In Portrait of My Mother, Hamid pays homage to his beloved mother who influenced him so significantly. In a less detailed fashion than his other two paintings, he has abstracted the most important parts of her essence in a simple yet dynamic juxtaposition of shapes and symbols. On the upper left we see his mother’s chin with the significant three tattooed dots facing upward; in the middle her henna painted index finger which was so instrumental to her weaving, and on the right, one of her rugs. The medium circle is his mother’s eye with which she views the world (larger circle), while the smaller circle is the eye that does not see. One is left to ponder whether the large round circle is indeed the world or another face of his mother with the reappearing three dots on the chin looking out to the world.

All Hamid’s works are painted in rich earth tones and are filled with meaningful and decorative symbols.

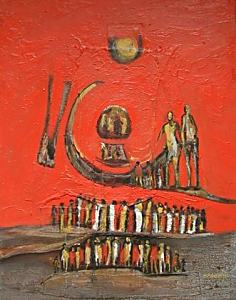

Dabo uses oils and gouache to paint ideas spurred by his social conscience, sacred forests and the spiritual world. Both his paintings here deal with the latter.

Together We Shall Go to Heaven gives one an uplifting feeling as two people holding hands are beckoned by another figure while two groups of people wait in the clouds. The way the paint has been applied lends a mysterious feeling to the composition.

In Accueil (The Reception) we see the textured orange red canvas dominated by the suggestion of a large ethereal figure in the background while groups of people convene, as if awaiting a prophecy.

In Baatine I and II, really a diptych, Diouf explores the vertical line as it is intercepted horizontally, the juxtaposition of shapes and how one small dot can emphatically punctuate the whole painting. Diouf’s esoteric paintings concentrate on the essential while giving us glimpses of every day objects that we rarely notice. The blue, black, white and gray of these compositions are in sharp contrast to the luminous yellows, creating delicate relationships.

He graduated from the National Beaux Arts Institute of Senegal, and has exhibited internationally.

In Trace of Old one is confronted with the monumentality of the ruins of the palace of Timbuktu. In the foreground the boulders are symbols of silent witness; the sky and sun testament to the unforgiving heat of the desert.

Seeing Beyond relates to the magnificence of the grand baobab tree also bearing silent witness but harboring a diviner at its core. This revered sage is symbolized by the all seeing eye, an important talisman in the Moslem faith, and cowry shells. Not only are cowries symbols of economic value, but they are used by the healer to read the future and divine the path a follower should take.

In both paintings one feels the harshness of the terrain through Njogu’s use of natural colors. Touray lives and works in Banjul, The Gambia.

In this small but stunning piece we see connections, indentations, interrelationships of color, juxtapositions of shades and movement of lines, all challenging the viewer to stop and interact with the work.

Glover loves to portray the vitality of markets and uses this theme often in many variations and color combinations.

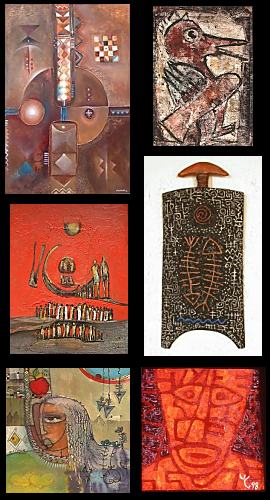

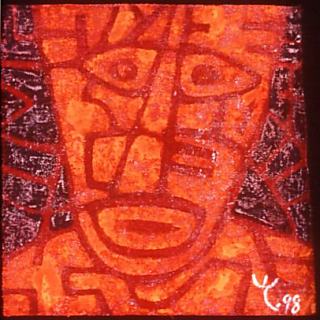

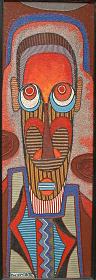

His three and two dimensional pieces, often of monumental size, have a fascinating textured surface. El Loko has developed his own pictorial alphabet with which to paint huge "cosmic letters". Here we see two of his "world faces", stressing a message of equality and universality. The puzzle–like pieces offers the viewers a chance to take the face apart and reconstruct it. They are, …"allegories which make no distinctions between race, sex, religion and identity".

El Loko seeks harmony, a global overview, and a global identity.

In the case of Empreinte (Mark), the discarded leather sandal with all its symbolism has become the focal point which he elaborates in the bottom half of the composition. There we see print-like forms seemingly stitched on to the main canvas. All the pieces are bound and glued together as is the old sandal, both images secluded in window box shapes, measuring the importance of one another.

Similarly, in L’Offrande (a gift), he juxtaposes a bundle of scrap cloth and twine with a small painting he has made and stitched onto the canvas. Both are offerings.

Almeida splits his time between Benin and France, traveling occasionally to the United States.

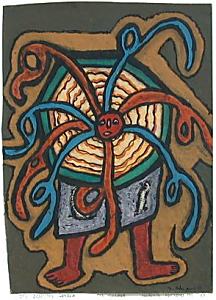

The Dancing Spider is a small painting showing the frontal view of a masquerader bedecked by sprawling legs emanating from the head which is framed by a web-like collar. The whole figure is punctuated by an outline of ochre while black lines define all the shapes.

Four of the people in Happy Family face the viewer with boggling eyes while a daughter seems to linger shyly behind the father. This painting is highlighted by primary colors; all shapes are again outlined in black, and patterns such as the small rectangles of the walls and pyramidal rooftops abound.

Although the son of a Muslim, Buraimoh uses many Christian themes in his work. In the two pieces here, however, one wonders if he isn’t questioning religiosity.

In The Priest we see a bust with an elongated face and a baboon snout, while in Three Wise Men we encounter three roguish figures; an arm reaches across two of the faces while the third sports a ring through the nostril. Indeed, what wise men are these?

In both pieces the bright colors of the beads glisten appealingly.

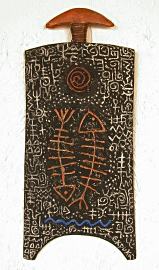

Victor employs nsibidi ideograms (an age old art of writing and mystical symbols from southeastern Nigeria), his own invented symbols, and stylized forms from traditional African art to develop a sensitive, unique way of using the ancient to express the contemporary.

In Fisherman's Story the bones are symbols for death and decay. Due to the pollution by multinational oil companies in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria, fishermen, once returning from a catch with stories of plenty, now come home nearly empty handed with tales of woe. The bones also refer to the social decay in Nigeria at the time this piece was painted.

Peace Offering with its dark blue abstract arms, reminiscent of those by Jacob Lawrence, offering up a white dove speaks to all cultures. The textures, curvilinear patterns and colors of Victor's compositions all enrich the visual experience.

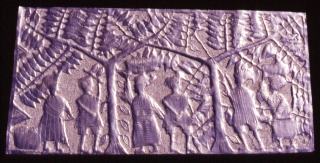

He was a ferrier who because of an injury had to change his vocation and first started working on this new medium by making small trinkets. Spurred on by success his pieces became larger and larger, some even becoming church doors. The sparkling quality caused by light hitting the raised details of the compositions and his interesting subject matter is captivating. He enjoyed depicting everyday life and fables from Yoruba lore.

Going to Market shows two women on their way to sell their wares while two hunters are busy trying to roust animals from the trees. Trees are a signature for Ashiru as the leaves truly glimmer from the reflection of light.

Egungun Festival, on the other hand, portrays masqueraders in two rows. They are larger than the people in the other panel because of their importance in society. Their presence is felt and the designs on their robes add to the majesty.

Olatunde resided in Oshogbo, Nigeria until his untimely death in 1998.

Here we see examples of the three former items. He instills his subject matter of animals, human figures or fish with humor and sophistication, encrusts them with a lively surface decoration and combines them in many different configurations.

Oladepo resides in Oshogbo, Nigeria.

Her bold starch resist wall hangings are reminiscent of her father’s bronzes but because of their larger scale they are more dramatic. The two animals on the traditional indigo blue cloth seem to be goats accompanied by a snake, common elements of the local countryside.

The larger panel of a woman carrying water and a tree with a snake in it speak to us of everyday life, the toil of fetching water and the ever present danger.

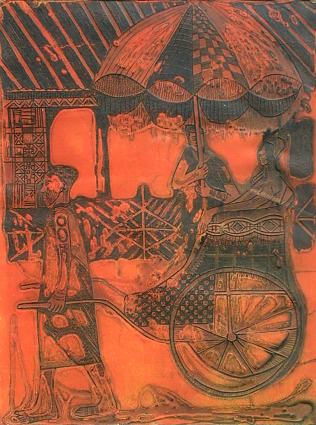

Superman II is a lino engraving by which the Japanese paper is stretched over the surface of the plate, depressed into the grooves, and rolled with ink, creating a subtle color effect. Here a superman holds up eight athletes in, "a kind of acrobatic game." The whole becomes a sculpture flanked by traditional designs on both sides.

A Ride in the City of Golden Dust, a deep etching, shows a dignitary with an attendant holding the umbrella above him being pulled on a rickshaw. Texture and design are important elements of Onobrakpeya’s work.

He has had important shows internationally and will be exhibited in New York next year.

Pelican shows the large profile of a dignified bird painted in rich earth tones while Old and Modern shows us a view of buildings in a village, also in somber colors. Both paintings exhibit strong linear details.

Chief Oyelami resides in Nigeria and has a large following in Germany and the United States.

Twins' works are teaming with details of animals, invented creatures, spirits, forests, villages and people. With pen and ink, gouache, markers, and dyes, he utilizes rich combinations of earth tones to compose his fantastic stories.

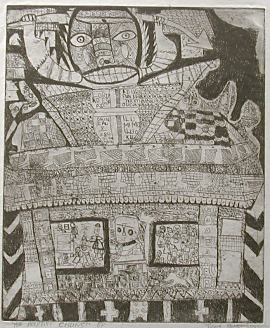

The Baptist Church in The Bush of Ghosts is one of his early etchings that was inspired by writer Amos Tutola’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. Here we see minute details, multiple focal points and spaces filled with patterns.

Villagers in a Collective Mood could very well mean that the man and woman in their canoe are off on a journey collecting what ever they come across! So far the boat is filled with a large coiled snake, crabs and fish, one of which is getting devoured by the snake. This piece is what Twins sometimes refers to as "pen’s dream" on masonite.

More recently he is using an interesting technique of appliquéd masonite on masonite. Twins has exhibited world wide.

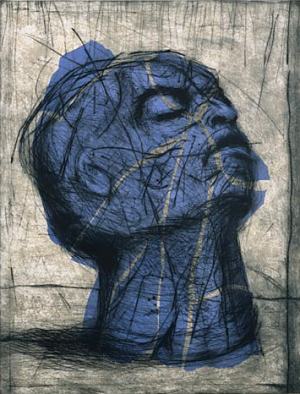

The powerfully expressive Blue Head lithograph with the skillful development of fissure-like lines and an unseeing or blind eye draws empathy from the viewer and leads one to arrive at his or her own conclusions. Still, and against all odds, the head with the elegantly proud profile is raised with dignity.

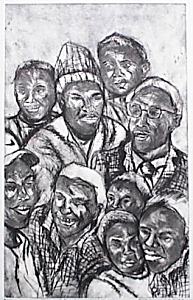

Distracted Lives, an etching from 1999, shows a group of people in conversation. So often, in pursuit of jobs, husbands have to relocate far from their families in order to support them… thus the title.

In Neglect we see three sets of legs interestingly interjected into the central terrain with the telltale empty bottle lying nearby. Both pieces are well composed and carefully printed.

In this painting of a family Roselyn speaks to the difficulty a woman has trying to achieve success in a male dominated society. She told me that she painted the woman in front being ridiculed by the man to encourage women to keep up the fight for stature rather than accept their prescribed societal roles.

The painting also delves into the role domestic violence plays in many families. Here we see the bewildered look of the daughter hoping for an explanation from the mother. Roselyn’s use of sand and string adds to the feeling of struggle and division.

The two ink drawings in this exhibition are from the 60’s during colonial rule.

Fantasy and reality collide in Untitled punctuated by monsters and captive slaves. In Sugar Sacks in Xinavane we see the heavy loads forced on the locals by the colonizers. Drudgery, suffering and evil are apparent.

Both drawings boil over with intensity, and team with staccato eyes and teeth. Malangatana resides in Maputo where he has his own museum.

The canvas explodes with overlapping faces, peering eyes and lines punctuated by three pairs of breasts and one lizard head. Boundaries seem to ebb and flow, parts of faces dissolving into other planes. Are the sections chards of broken hope waiting to be reconstructed? The blues and purples give the painting a mysterious feeling while the red and gold lightening-like lines in the top left corner and pink throughout highlight the composition.

A strong humanist, he is a master at expressing evil and anguish. As Jean Kennedy states in New Currents Ancient Rivers - Contemporary African Artists in a Generation of change, "……color and form plumb the depths of physical feeling."

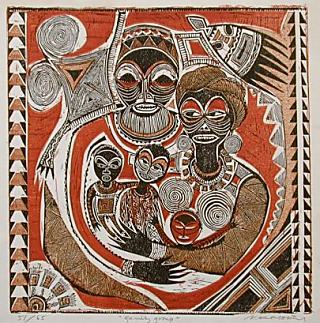

Family Group, at first glance depicts the archetype unit, mother, father and three children, unified by an embrace. However, looking at their faces, we see scowls and mask-like attributes; fear and distrust now pervade the composition.

Bastion of Apartheid is an even more powerful statement as we see people tortured and maimed by the white authorities while the skeletal priest and his brethren, also white, turn their heads in prayer. Terror grips the black South Africans.

In Self Portrait Mbire uses bold strokes of color to accentuate the rather distorted face and question identity as well as beauty. Like several artists of the 90’s such as Basquiat and Keith Haring shock value is used to jar the audience into taking a stand on the art.

Untitled's rich palate, patches of white highlighting and undulating forms underscore the seductive nature of the painting. In describing this piece, Sane refers to it as a "part of nature" -- a jumble of men, women and animals experiencing natural emotional instincts.

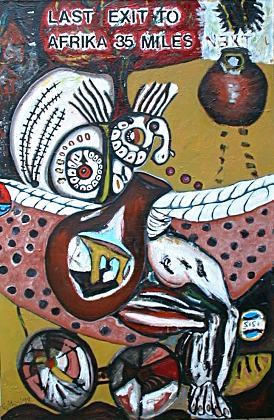

Leisure Rider, a mass of bodies, heads, chains and wheels, "is about people who love to lean on others without sweat." As a rider you give up control and are carried, unthinking, into unimaginable situations. In this instance the rider has become embroiled in a political scenario that has him and many others caught in chains. When one stops thinking, one cannot escape. It is only in the moment you start thinking again and become a rebel that you have a chance.

Both paintings challenge the viewer to a closer study in order to decipher where one figure starts and another finishes as shapes meld into each other, defined only by black lines or shadows. In both, emotion speaks through the eyes.

An interesting anecdote about Sane is that he gave himself the name "Sane" when he quit his teaching job, abandoning the stability of a regular salary, to become an artist. The new name was in reaction to his friends saying he was "insane" to do that!

Gossip on Wire depicts idle women passing their time talking about this and that because they have nothing better to do. The moral of the story being, "It is better to occupy yourself than to just go around gossiping."

An example of this is Sanaa’s, Secret Meeting which is painted on paper he made, collaged with bark cloth and framed with a bark cloth backing over the wood superstructure. The blues, yellows and greens in this painting all have a jewel tone quality.

In Sea Festival, also painted on a piece of handmade paper, Sanaa uses a gentler juxtaposition of pinks and greens on the sails of the boat - perhaps to portray ethereal spirit entities dancing rhythmically in the billowing wind.

Cross Road, on the other hand, is a bold assembly of collaged shapes symbolically stitched on to the background.

Her symbolic sculptures of textured mahogany and gypsum, at first glance give reference to the work of Henri Moore through their beautiful brevity. They are universal shapes but they are also very African in nature. The allusion to ebony and ivory is just one connection.

In Untitled there is a definite affinity to a woman’s body and all the symbolism that that conjures up such as fecundity, voluptuousness, maturity, motherhood, et al. Balance, an important element in all of Adis’ pieces is both bold and delicate here, a symbol in itself.

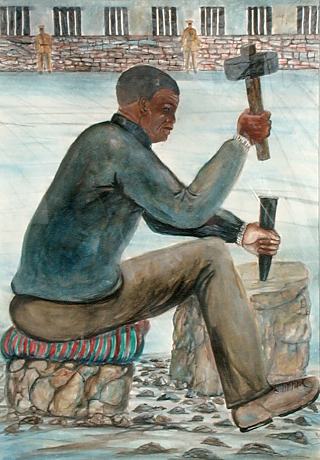

In her four evocative paintings she speaks to us of man’s inhumanity to man. Confinement l elaborates on a difficult theme and asks the viewer to consider all the ramifications of the term and how it impacts mind, body and spirit.

Exodus demonstrates powerfully, yet minimally the drain or break up of strength and power as people flee from their homeland because of war, politics and death.

Faces of Ethiopia, a build up of acrylic on acrylic, touches our hearts as we see the sorrowful eyes of four faces peer out from behind the tangled web. For Sofia, "Ethiopia speaks with the eyes, icons and crosses."

Sofia now resides in the United States.

His work is distinguished by canvases full of detail, calligraphic symbols and panes of rich color. As Kennedy wrote in her book, "Drawing on the wealth of calligraphy in the ancient liturgical languages of Geez and contemporary Amharic, each with alphabets of several hundred symbol characters, Wosene uses them like tracers to re-assert the authority of history."

His painting Family Portrait lll brings to mind the work of Wilfredo Lam of Trinidad in its rich coloration and intricate layers of detail highlighted with punctuations of red. On careful inspection a group of figures wearing masks seem ready to march forward out of the painting.

In Bed 8 we see a stark metal bed covered by a white sheet with a bare black light bulb hanging over it – the bare necessities.

Bed 12 looks a little more comfortable, but the person in it, with his head on the bars, seems ill at ease to say the least. What is comfort? Perhaps the newspaper shadow behind tells the story?

The well known Writer/Art Critic, Ulli Beier has said of Salahi that, "No other artist could create a more perfect synthesis of the cultural elements that make up modern Sudan, the Islamic tradition and the wider all-African orientation of today."

El Salahi now lives in England.

His Protected Gate is reminiscent of the architecture of the Nubian house where one frequently sees the abstracted forms of the crescent and cattle horns adorning the building. He has reminisced about seeing the oil lamps in the windows of the homes as faces from a distance.

Nour enjoys juxtaposing utilitarian objects and architecture in his very modern pieces.

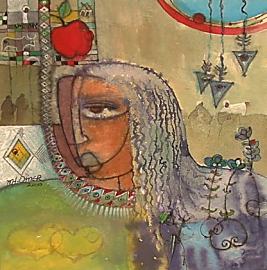

Being a devout Sufi, Mutasim believes that people need to love and accept each other, and above all that the younger generations need to learn to discuss and carry on dialogues so that they can better understand each other. Mutasim uses many symbols in his work and as you view his work, you are immediately confronted with a sense of mysticism. In Migration figures appear and disappear into the background; the ancient village is shrouded in purple-gray fog, and the prismatic colors on the left, the birds and the flowers give an uplifting feeling of hope.

Adam and Eve and First Love both display Mutasim’s affinity for a gentle feeling, his pervasive use of symbolism, and juxtaposition of intriguing colors.

The large drawing, Egypt, portrays a beautiful but angry mother in front of an inverted pyramid. She is intensely focused on something other than her disappearing daughter who is falling into the abyss of a whirlpool below her.

The second, smaller drawing, Fear, shows a woman trapped by her fear, afraid of someone or something. Both pieces show a mastery of her technique. The flowing lines and soft shading create a mysterious mood in which fantasy and reality intersect.

In the etching, Landscape, we see, "… an imaginary world where all the lonely people live."

Naglaa’s inherent style is the use of sinewy-like roots which swirl and entwine – embodying struggle - similar, to the ones which envelope the girl in Fear.

At first glance, the rich colors and textures in Mirage give the appearance of a lavish textile fragment. On closer viewing, however, one is drawn into the center where the dunes of the ever changing desert radiate electrical charges and suggest an oasis of buildings in the foreground. "A mirage is like a very dangerous game. That is why that part of the painting is bejeweled or decorated by a fanciful border – 'check and mate'. One can win just as one can lose!!"

Feriel has a degree in architecture, thus the fine tuned appreciation for space and embellishment.